The American Experience versus Nationalism:

A reply to Rich Lowry and Liah Greenfeld

Economics (and Politics this time) Without The B.S.**:

[** Double entendre intended.]

Rich Lowry and Liah Green feld had a discussion on American Nationalism for the NPR program 'On Point'.

https://www.wbur.org/onpoint/2019/11/05/rich-lowry-the-case-for-nationalism

This is my reply:

This

discussion by Rich Lowry and Liah Greenfeld is disheartening; neither gets to

the core component in explaining what has driven human development, DEMOCRACY,

simply defined as the ability of people to govern themselves. Democracy has not been sustained by

nationalism, or even American Nationalism; it is the American Experience that

has sustained the democratic urge of people, both in this nation as well as

around the world. But these are not

American values, in the sense that only Americans can promote them, these are

universal values that anyone can aspire to.

So let’s

review the historical record to set the argument. The largest geographic empire on Earth was

the Mongol Empire (of many nations) of Genghis Khan/Kublai Khan; but the one

that had the greatest influence on us [so far] is the Roman Empire (also of

many nations) because it was that system that emphasized universals that we still

acknowledge today and has been the underpinnings of the Western Culture which

has predominated over other cultures. When

the Roman Empire collapsed those universals were carried in the institution of

the Catholic Church. When the Catholic

Church emerged from the Middle Ages with a fractured Europe which stopped the

advance of the Islamic influence and Mongol Empire, was faced with the Protestant

Reformation following the Renaissance, and latter developments in the

Enlightenment, Age of Reason, Return to Nature; this thread in history can be

characterized as the advance of humanism to the very present. However, there is a distinct marker in this

advance of humanism, DEMOCRACY!

Why does the

advance of humanism from the Renaissance stall after several generations and is

followed by short bursts of energy followed again by more repression over

several more generations? It is because –

as noted by Kenneth Clark in his ‘Civilization’

series in the late 1960s – there was no weight to this movement because the

benefits only served a select few in society.

It will take the impulse toward democratic governance to sustain the

benefits that come from the humanistic movement.

It is the

American Revolution which stands out in this advance of humanism. For people to succeed in governing themselves

there must be a system of governance that promotes the general welfare and must

have some sense of fairness that all who are subject to that governance are

willing participants in the system. We

must recall however that the American Revolution was immediately followed by

the French Revolution in Europe that was also promoting democratic rule. But the influence of the French Revolution

has had difficulty in promoting democratic values throughout the 19th

Century and even well into the 20th Century; unlike the influence of

the American Revolution which has met challenges like Manifest Destiny, the American

Civil War, Industrialization, the Great Depression, World War II somewhat

successfully. Why the American

Revolution and not the French Revolution in Europe for advancing the case for

democracy?

The value

system embedded in the American Revolution is an inclusive one; but, it did not

start out that way, and you can even say we have been dealing with this

inclusiveness or the lack of it ever since.

Who gets included; who gets left out?

While the American Way has not had the difficulty in succeeding like the

French Revolution in Europe, the American Experience has been characterized by

a continual re-examination of its values through the various generations with a

renewal of liberty as articulated by President Lincoln in his Gettysburg

Address.

At the core

of our American Experience are:

(1) the

conflicting values as expressed in the Declaration of Independence, especially

individual liberty and equality as played out in the commons;

(2) the

fragmented political structure of our federal system (national government,

state, and local and regional government bodies) with representative government

characterized by checks and balances throughout that structure;

(3) an

economic system of free enterprise that promotes and rewards individual

initiative and creativeness in providing the wants and needs in a society, and

can concentrate economic power with its resultant influence in the political

sphere;

(4) and

a process of governing that includes civic engagement of the people which

constantly requires the building and shifting of coalitions to interface with

that representative governing structure;

(5) all

to coalesce with the Will of the People somehow being expressed so that

progress can thrive.

In short,

unlike the European view of democracy that comes from the influence and spread

of the French Revolution, that looks at democracy by holding people to high

ideals, the American Experience is a dynamic system not a static system that is

constantly re-evaluating our values to fit contemporary circumstances so that

what results are practical solutions although they may be imperfect and subject

to change at another time. Our bedrock

foundation is in the process, not some ideal view of society; life is in the

living, in the journey; the process of life is about change. Our American Way is about adapting to change.

Furthermore, we came late to realize

that to preserve our democratic values they must be the basis of our national

security strategy as we engage the rest of the world. This is not globalism; this is pursuing our

self-interest, an enlightened self-interest that we spread internationally by way of

alliances with like-minded allies. We

engage the rest of the world not because we think we are better than others but

because our economic system tells us that promoting the general welfare

involves us in engaging the rest of the world in the allocation of resources,

scarce resources, in the most efficient and productive manner to secure the

very best for all who participate in this sort of behavior.

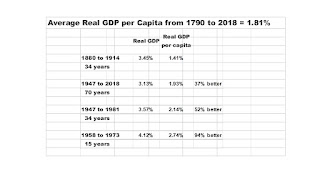

Following the 1960s we have failed to promote higher rates

of economic growth; higher rates of economic growth gave us the vitality our nation needs to address new issues of social

justice, that greater vitality in our economic sector gives us greater vitality

in our political sphere to address issues that should be part of our public

policy agenda. Instead we have settled in for maintaining the status quo with

growth, but much lower rates of growth and therefore less vitality in our

economy and our society. We emerged from World

War II by

putting ourselves on the world stage for the first time as the world leader. That world back then, and still today, needed

[still needs] democratic leadership to promote peace and economic betterment. To make change we need to invigorate vitality,

economically and politically. Our lower

rates of economic growth are not enough to overcome the built-in inertia of the

status quo to make the necessary changes for remaking the world order into a

more peaceful and democratic way of living. Our national self-interest is vested in our

ability to make those changes.

The

study of history is influenced by the social movements that affect people at

any particular time. So in our history,

the role of the individual in a society and the role of government in that

society, the expansion of the American nation westward and the conflict of

cultures between a native inhabited people and new settlers, slavery and civil

rights struggle, the industrialization of the American economy from a

rural/agrarian economy along with labor/management issues in a corporate

setting, immigration, the participation of women in society to include

politics, are all topics , among others, that get discussed and can be

influenced by the particular generation that deals with these issues. The American experience is a unique

experience in the historical context.

The fundamental principle of our nation’s founding was that people could

govern themselves. We are not the oldest

democracy; and, we are not the only republic that was ever created. But our founders did create a system for

governing with the consent of the governed while respecting dissenting opinions

– a constitutional, democratic, republican form of government.

An

understanding of American history does not come naturally. It takes effort. Our diversity can pull us apart. We have had a historical common thread as one

nation, with its faults, but never-the-less with progress shown. For the most part, the American people

through history have not been won over by an idealistic notion of

existence. Americans, for the most part,

have been a practical people who have fumbled their way forward, sometimes

making mistakes, but ever trying to right the way and do a practical justice

for their forebearers and progeny.