The Gold Standard

(and Monetary

Policy in general):

Or just because the lubricant can

seize the engine doesn’t mean that it drives the engine

Economics Without The B.S.**:

[** Double entendre intended.]

I must respond to a recent James Grant op-ed in the Wall

Street Journal [https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-fed-could-use-a-golden-rule-11562885485?mod=e2two] this past week where he is using

President Trump’s appointment of Judy Shelton to the Federal Reserve Board, who

is an advocate of returning to the Gold Standard, as an opportunity to

criticize the capriciousness of our monetary policy since Nixon decoupled gold

from the dollar and internationally we have allowed currency values to float

against each other on a daily basis. The

esteemed Mr. Grant, like many monetarists, has the economic engine confused

with the lubricant needed to keep it operating; overlooking just who/what is

doing the driving and is responsible for performance. While money is a necessary resource it is not

the key determinant in the performance of an economy providing for society’s

needs. So let me take off my Carhartts

and exchange my Red Wings for something lighter and more comfortable as I

attempt to diagnose Mr. Grant’s thesis and enlighten him on the nature of a

work effort, which after all is what we are talking about when we discuss

economics, the allocation of [scarce] resources in an efficient and productive

way to accomplish work.

What Mr. Grant gets right is that gold is the international

standard of value for money; it sits at the apex of the hierarchy of money –

gold, paper money of a sovereign, bank notes, credit instruments, etc. What he gets wrong, along with other gold

bugs, is that gold has no intrinsic value in and of itself. It’s value is determined by its use and what

it represents, which has been since the Napoleonic era the primary country

backing the gold reserves of the world – the British pound sterling through the

19th Century up to World War I and the U.S. dollar after World War

II, with the world in a bit of uncertainty during the interregnum of the 1920s

and 1930s. In other words, gold is no

more than a sycophant to the best performing economy in the world as perceived

by others. Using gold, or any other form

of money, is just an artificial value representation of work. Aside from money’s use for payments, it

provides the float system, the grease if you will, necessary for intermediaries

to make markets between those that have money to lend and those that need money

to operate.

The other point that Mr. Grant gets right, but he is

critical of the point, is when he says, “Gold-standard

central banking concerned itself with the present. Millennial central bankers

dare to take a view of the future.”

Money is found in human societies when they become civilized, no longer

living like the rest of the animals; but living in groups, exchanging goods and

services, and having some concept of a future existence. Interest rates fundamentally represent the

concept of a future and the value and costs associated with that future

compared with the present.

Mr. Grant yearns for a return to

the gold standard and laissez-faire; but, since World War II as the U.S. has

emerged on the international scene in an activist role to spread its values of

democratic liberalism and enlightened self-interest primarily through its

economic and diplomatic activity backed by a strong military presence, the

world has become more democratic, trade has replaced colonialism, and economic

growth has fostered a faster pace of human betterment than any prior historic

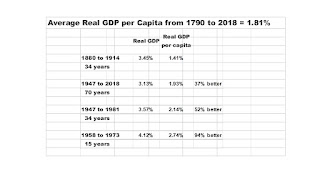

period in the same amount of time – even bettering the 34 year period of 1880

to 1914 of Arthur I. Bloomfield’s reference by Mr. Grant

with a period twice that during Messrs. Bloomfield’s and Grant’s (and my)

lifetimes 1947 to 2018, 70 years with a Real GDP per capita (factoring out

inflation and the effects of population) 37% better, 1.93% per year versus

1.41%; the 34 year period 1947 to 1981 with 2.14% was more than 50% better; and

the 15 year post-Sputnik period 1958 to 1973 was almost double the growth rate

at 2.74%.

During this period policy makers have become

more adept at gauging the rate of international progress while maintaining

moderate growth without the wild swings in the business cycle that characterized

the 19th Century.

Mr. Grant expresses concern about the vagaries

of human decision making, but a call back to the days of laissez-faire does not

eliminate or lessen the consequences of human error, especially in a world

order so interconnected in a way not envisioned in prior eras. It is the use of credit that characterizes

our economy today. The gold standard was

a rigid system for managing a modern economy.

What we need and have is the ability to expand and contract credit in

relation to the rate of growth. We

haven’t eliminated the vagaries of the human dimension, but we have managed to

provide better management of the national and international system.

If there is to be a criticism today it would be

in how we manage the trade off between economic growth versus economic

stability. I think a premium has been

placed on stability while sacrificing growth, probably because policy makers

realize the lead role the U.S. plays internationally where monetary policy set

by our Federal Reserve causes others internationally to react to it. But here in the U.S. that slower growth rate

has led to a less dynamic society which has bred growing income inequality which

has had negative effects in our political arena. Where Mr. Grant advocates for the supposed consistency

that comes from the gold standard, I advocate for more dynamism in our economic

policies which also provides much needed vitality to our political system. This very point was made this past week in

another op-ed but in the New York Times by historian Lizabeth Cohen [https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/10/opinion/affordable-housing.html] recalling the days of a more active federal government role

for fiscal policy in achieving public policy objectives where relying on the

private sector has been lackluster.

Money does not drive economic growth, people

do. It is the work effort of people that

determines output. If you have three

businesses, identical in every way – building layout, number of employees,

making the same product or service, etc. – and you fund each of them to their

needs; you will not get the same performance for each of them, one will be

better than another. Money is a stop/go

decision; it is not the determinant of performance level. Monetary policy is a blunt instrument;

whereas fiscal policy, especially investment, can be tailored and targeted to a

specific goal. It is money coupled with

human effort that determines our economic output; and, that is why the public

sector coupled with the private sector have produced the greatest broad-based

growth during the post-Sputnik period to the early 1970s and even beyond. And that is why the standard of living in the

Free World pulled away from communist systems during this period which

eventually led to the collapse of communism in Europe.

No comments:

Post a Comment